The Alternative is Unacceptable

Singer 0:00

Stop, talk to me.

Crystal Page 0:10

Hello, Grant

Grant Oliphant 0:12

hey Crystal

Crystal Page 0:13

welcome back.

Grant Oliphant 0:14

Hey, welcome back to you too.

Crystal Page 0:15

Thank you.

Grant Oliphant 0:16

You beat me to it. Yeah. Welcome back to stop and talk. This is our third season. It's actually also a special series in our third season where we're focusing on the issue of the sewage crisis and pollution in the Tijuana River Valley. And actually we just had an amazing set of conversations with people who are working in community on this issue. But I wonder if we should say a quick word about why this issue matters to us.

Crystal Page 0:45

Yeah. I mean, I think for anyone who's grown up in San Diego County, no matter where you've lived, you should know that it's not just a bad smell in South County, it's that there's actual sewage in the water, and even though it hasn't all been proven, we know that there's an issue, and these folks are gathered together to organize and speak out about it, because everyone deserves clean air.

Grant Oliphant 1:10

Yeah, and what we're learning is this is a significant public health issue. We're learning that it's a significant economic issue. We're learning it's a significant lifestyle issue. Actually, we hear a lot about that in the interview, so I don't think we'll go on. But if San Diego can solve this problem, not only will we solve a problem that's been around for far too long, but we will prove to ourselves that we can take on really big, hard things and solve the problems that others think are insoluble. So I'm excited about the work in this area, even though the problem is tough, and that's why we're doing a special series on this

Crystal Page 1:45

and to build on what you just said, when San Diego solves this problem,

Grant Oliphant 1:50

yes

Crystal Page 1:50

we will know we can do hard things, and we will continue to do them. Right?

Grant Oliphant 1:54

exactly.

Crystal Page 1:55

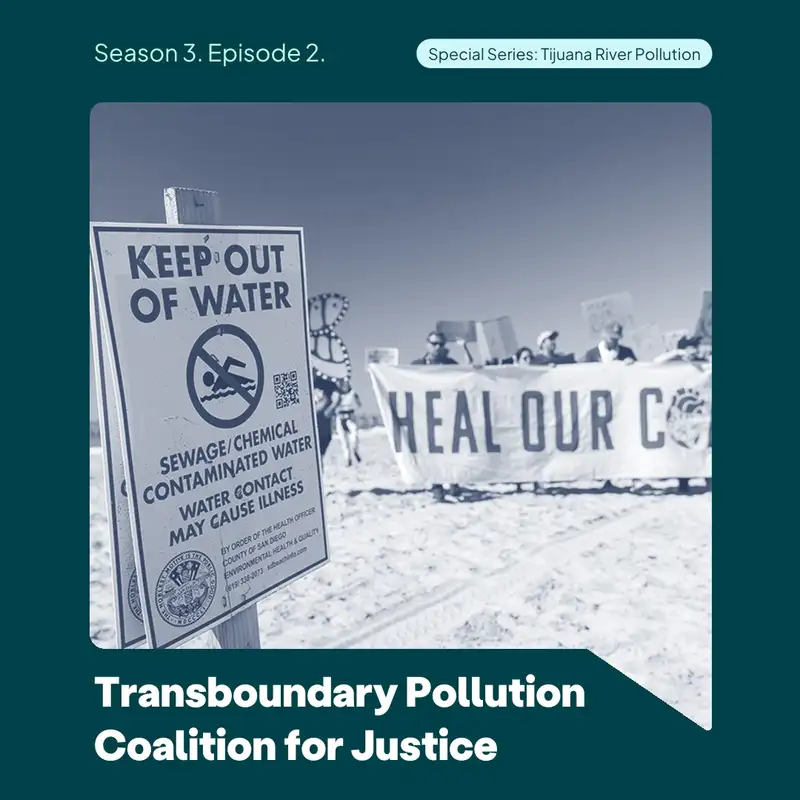

So today's guest, we're super excited to welcome the Transboundary Pollution Coalition for Advocacy and Healing.

Grant Oliphant 2:02

You did that well, it does not come trippingly off the tongue, yeah.

Crystal Page 2:07

But this handkerchief shows the artwork, the culture, the connection that folks are making with their love of the ocean, the one of clean water and clean air.

Crystal Page 2:15

Yeah. And so our our interviews were, we did a an interview with two folks up front. Why don't you describe who they are?

Crystal Page 2:23

So we have Ramon Chairez with un Mar de Colores, and he's the Director of Education and Environmental Advocacy. And what's great about Ramon is, if you go to any of the organizing events, he is a voice from the community with the community who's constantly organizing, because it's just his friends and neighbors, right? He wants things to feel warm and connected. We talked to Sarah Davidson, the Surfrider Foundation, Clean Border Water Now. She's the manager of that let's get that clear. And Sarah is oftentimes that quiet presence who is a great writer and organizer, and you can tell she feels everything in her heart, but also just a really good community organizer who starts with, you know, climate justice, Community Justice, but, but you can tell that she's in this for the long haul.

Grant Oliphant 3:09

Yeah, no kidding. And then we spoke in the second half with Lesly Gallegos-Stearns, who is the volunteer and Outreach Manager with San Diego Coast keeper and with Kapili Pasa, who is the waterfront manager at Camp Surf, and that conversation was so enlightening in terms of how they see the challenge with reaching not just young people, but people of all ages in community, and why it matters to them personally. I think, I think all four of these folks leave their heart on the table in terms of sharing with us why this issue matters and what we can do about it. I'm excited to share their perspective. So why don't we do that?

Crystal Page 3:13

Let's dive in.

Grant Oliphant 3:13

And we'll come back later.

Grant Oliphant 3:11

Ramon, I want to start with you with a question that I want to ask both of you, which is more anchoring our listeners and viewers in an understanding of why this issue matters to you personally, and what is it about your background that brought you to the work? We'll talk about your organization in a moment. But first, you as a human being. Why? Why are you in this work?

Ramon Chairez 4:23

Well, as you were outlining the question, I started to get emotional. I grew up next to the river valley. When I was 14, my parents moved us from LA to San Ysidro to some apartments that were hugging up against the river valley. And it was the first time that that me and my siblings had access to such a vast natural space, whether it was the river valley or the estuary or the the ocean. So we we did not grow up around that kind of nature outside of parks and. Yeah, and so that river valley became a place of exploration for me and my brothers. And then throughout the years, you know, I learned how to surf in IB when I was much older, that became a special place. I learned the basic skills of farming in the river valley at Wild Willow farm. I started to volunteer there, and so I really started to develop an appreciation and a relationship for that entire space.

Grant Oliphant 5:27

Yeah, so this issue for you is deeply personal. Going a way back.

Ramon Chairez 5:28

It's personal. It took me a while to kind of come to that realization. You know, it was, it was through the work with Un Mar de Colores and then just being connected to the the community that does incredible work in the river valley, including Sarah and Surfrider. And it was, it was almost like a calling. I also have a really close relationship with, um, with Waylon Matson over at four walls International. And, you know, he's been a guide for the for me, as far as understanding the complexities of the river valley on both sides of the border and and the last thing I'll mention is that, you know, the most vivid memory I have of being introduced to the river valley was my father having to cross the border whenever he visited my grandma in Tijuana, we always knew he had gone, because he would come home and his his legs, his pants and his boots would be muddy. And so we knew that he had just crossed the river valley. And it was like this unsaid understanding, like because, you know, we knew he wasn't documented. My father's been crossing that border since he was a teenager. So for him, you know, the border didn't really, I don't know, I don't know how to say it, but for me, it was like a small obstacle to have to jump a fence and then cross through the river valley. So that recently, when I've spent more time there, I keep thinking about that memory and what that border means to me and my family.

Grant Oliphant 7:06

Thank you for sharing that I'm that is a powerful image that's a podcast in and of itself, and we'll probably come back to that, Sarah, I want to ask you the same question you have a background as a marine biologist, so in some ways, it's natural that you care about an issue related to water, but what's your connection with this issue?

Sarah Davidson 7:32

Well, I'm not from this area originally. I've been here for a little over two years working on this issue, but this is my home state. I was born and raised in San Francisco, and I've worked in many trans boundary watersheds where there's an environmental justice component, and I find that there's always an opportunity for cooperation where it may seem that conflict is the default, and so I guess I am. I'm drawn to this issue here, in in the opportunities it provides to really address the heart of the environmental injustice going on and sort of reframe the way we look at this, you know, somewhat problematic watershed and the way it's being managed.

Grant Oliphant 8:44

So, you know, I'm thinking about with the folks who are watching this and learning about the issue, maybe for the first time, and or listening to the podcast and maybe learning about who you are for the first time. We're privileged to know and support your work, but they may not know about what you do. So I'd like you both to say a little bit about your organizations and how they're active in this issue. Sarah, why don't we start with you?

Sarah Davidson 9:12

Yeah. So I manage the clean border water now program at the Surfrider Foundation, and I work through the San Diego chapter, which is just one of over 200 chapters that Surfrider has across the United States. We're a national nonprofit aimed at protecting the world's ocean, beaches, and waves for all people through a powerful activist network. And we're really driven and led by volunteers on the ground, who are, you know, quite passionate and want to advocate for the places they care about. And that's really how Surfrider started working on this issue, almost 30 years ago now, was local residents approached us with an interest in. Trying to address this problem, and we've been investing resources and staff time in it ever since, because it is such an important place to so many people, and yet it's doing harm to so many people.

Grant Oliphant 10:14

I just have to draw or underline something that you just said, which is 30 years, and a lot of people don't know that this issue has been around for decades. And if they do know, they actually think that it's chronic, and there's not much we can do about it. So we're going to talk about that and why that is a self fulfilling prophecy, and I hope you will both tell us why that's wrong in the course of this conversation.

Ramon Chairez 10:42

I mean, we should talk about that, because we you hear that phrase a lot, decades, decades. But what does that really mean? And if you do just do some basic research on the river valley and how it really developed in the last 100 years, it was very clear from the get go that establishing residences or businesses, for that matter, that was a flood zone. It's a flood plain, right? It's an intermittent River, and so when it rains, it's going to flood with water, and the the areas around it were developed despite knowing that.

Grant Oliphant 11:19

So there's a there's an infrastructure basis for what's been happening, yeah, for a long time. Tell us a little bit about your organization, Ramon.

Ramon Chairez 11:30

I work for un mar de colores, which means an ocean of colors in Spanish.

Grant Oliphant 11:34

It's a beautiful name.

Ramon Chairez 11:35

Yeah, I love it. I was super drawn to it when I was first introduced to the organization, and the potential for working for Mario ordonis Calderon, which is our co founder and executive director. And he started this about three or four years ago, and it was a simple vision. You know, he was growing up and not growing up, but he was living in Encinitas, new to the area around a lot of Latino kids, you know Mexican immigrant kids that that he never saw in the ocean, and so he wanted to create access, and that's how the org was born. And so we do a lot of environmental education, ecological literacy, and we do it mostly through surfing and through eco therapy. And we've become involved with the Tijuana River Valley because we started to expand, and we wanted to have a South Bay chapter and invite kids from the South Bay into the org. And, you know, we, we didn't have anywhere to take them to surf. So while, you know, you'll get sick, especially for kids, if you're working, you know, we work with kids from six to 18, but our flagship program works with six to 12, and so those are kids that should not be exposed to that kind of those conditions in the water.

Grant Oliphant 12:53

So, Sarah, I'd love to hear from you the the, you know, what is the nature of the crisis and and then Ramon, I'd love for you to pick up on how is it affecting communities, and you both can talk about both aspects of this issue. But why don't you start? Ramon? You follow. You want to start?

Ramon Chairez 13:13

Yeah. I mean,well, let's just jump right into the to really what's happening right now is we have an open sewer, and we've allowed that to happen, you know, and and having that open sewer, you know, creates a whole array of issues and problems. You know. We can talk about the environmental challenges or the ecological crisis happening in the river valley, but we're also really focused right now on what the public health hazards are, the risks, and we know that they're there. And that's that's been the biggest challenge, I think, for the task force, is it feels like a battle, like we're at- I don't want to say war. I don't want to use that word loosely, but it does feel like we're like everyone's kind of bunkered in their positions, and we're all, you know, strategizing on how we can elevate this issue and find deep, true solutions and and it's not like the plans aren't there. It's more like, it's like we're we're having to go uphill, fight uphill, against agencies and institutions that should be supporting us. And that's, that's the biggest thing that pops out right now, is like, there's a lot of wonderful work being done on the ground with binational organizations and leaders and, you know, different agencies, but at the same time, the challenges are coming from the institutions that have the most resources, right people that. Can actually fix this issue so

Grant Oliphant 15:02

and if we can touch on why that is, it would be good, you know, I have to confess that, as you were just saying, what you were saying, what was coming to mind for me is, this is a pull my hair out moment, and I don't have a lot of air to pull out. You know, I am puzzled by why this. It wouldn't be obvious and clear on the face of it, that it's a public health challenge, and has been for decades. When I arrived in town two and a half, three years ago, my first encounter with this was people dismissed it as a surfer issue or a beach issue or a lifestyle issue, and anybody who knows anything about man made sewer systems, open sewers. To your point, Ramon and public health knows that the single greatest advance in human history with respect to public health was actually safe, contained public sewer systems. So, so we're, we're violating the fundamental rule, and it's kind of obvious that it's as

Ramon Chairez 15:59

basic as that, right? Yeah, it's, yeah, it's plumbing, right? I mean, why are we talking about it? Why are we, why are we allowing the communities that live alongside the river valley to endure that? Why is it up to the community to prove to everyone above us that there's a issue here? That's what it feels like, like they, they're putting the burden on us so, like, prove to us that your community is getting sick.

Grant Oliphant 16:26

Yeah. So, So, Sarah, we've leapt way down the road. Can you bring us back to the problem and so that we can put some parameters around what, what it is that we're talking about? Sure, yeah,

Sarah Davidson 16:42

well, in a nutshell, I'd say it's one of the worst ongoing environmental justice and public health emergencies in our country. Right now. It's, you know, it's getting worse every day. There's 10s of millions of gallons of untreated sewage, industrial waste and trash flowing through the Tijuana river every single day that is impacting not only water quality, but air quality. There's new research now that that is giving us more insight into exactly what some of those air quality impacts and resulting health impacts are it used to be that we thought that some of the worst public health impacts were happening right at the coast where the sea spray was entering the air and causing health health impacts, not only from people entering the water themselves and exposure that way, but just from breathing in the water on the beach. Now what we're coming to understand is that communities far inland, you know, communities like Nestor and San Ysidro and others, are near hot spots where hydrogen sulfide gas is resulting from rapidly moving water, and the turbidity in the water, these bubbles pop, releasing gasses into the air in a process called aerosolization. And researchers have found hydrogen sulfide gas at unsafe levels for quite a long time now, and we expect some of that research to be published very soon, so I'll see some of that those results. But,

Grant Oliphant 18:24

and this is an unexpected aspect of this. You know, in previous conversations, not unexpected for people, I've seen the two of you looking at each other, you know, the I have seen news accounts where it's dismissed as an odor issue and and the and the reality for those of us who know about noxious gasses, and I know far less than you do, but I know that that bad smell suggests a bad contaminant potentially in the air, and

Ramon Chairez 18:52

your instincts tell you, if you're smelling something Yeah, wrong, right, there's something wrong there, right?

Grant Oliphant 18:58

Yeah. So talk about the community impacts both of you in terms of, if that is Sarah, you described it as one of the worst public health emergencies in the country. And I'd love to know why California won't declare it an emergency, because it clearly is, clearly, even though it's chronic.

Sarah Davidson 19:21

I mean, if this isn't an emergency, I don't know what is right.

Grant Oliphant 19:23

So let's describe for people the nature of the emergency that's happening on the ground. How are communities being affected, and what are people who aren't being living this issue day in and day out, not seeing, not hearing. Tell us a little bit more about that.

Sarah Davidson 19:44

You mentioned the odors, and that is certainly one of the most noticeable impacts of the hydrogen sulfide, is that people wake up at night because the odor is so strong, people aren't able to open their windows in summer. Months when the heat is unwilling crushing, the odors are giving people headaches, all kinds of other health impacts, gastrointestinal issues. Children are experiencing higher levels of asthma. School Reports from school clinics of new onset illnesses in children have increased over recent months. The health impacts really go on and on, and I'm glad that you're going to have a chance to talk to some doctors to learn more about those so that is certainly one aspect of the community impact, but I think also one that goes untalked about often is the mental health aspect of living in this crisis, day after day of, you know, calling for intervention from those with the power to do so, and being ignored, being told that it's not an issue, I think just having to endure these often nauseating odors day in and day out, and not being able to escape them definitely has a mental health impact that we should be talking more about.

Grant Oliphant 21:16

So interesting.

Ramon Chairez 21:17

Yeah, I'll add that despite whatever some of our public agencies say about the issue, they don't know how long that that the hydrogen sulfide has basically been in this space. You know, we can do the math in our head, and we know that it's been there for at least four or five years, if not longer, in terms of the levels that it's at right now. And so they can't tell you what the long term impacts of a community being chronically being exposed to hydrogen sulfide, even at low levels, whatever levels that they're referencing, those are levels that are in place, or standards that are in place for, you know, for industry, yeah, for wastewater treatment plants, you know, with people that have PPE on, like, protective gear, not, not for neighborhoods, no, yeah, no. And so I it's, it's hard for me to listen to some of the stuff that I hear from I might as you notice, I'm not mentioning any names, but think we can all deduce who I'm talking about. It's hard for me to listen to them, to them report on this issue and with confidence, it's like, it's, it's, it's,

Grant Oliphant 22:35

why? Why are you getting that pushback? I'm curious, from your perspective, you know, dealing with the science, being advocates in the community, living in the community. Why? Why are you getting that pushback? Do you think?

Ramon Chairez 22:49

Well, I think there's different ways to answer that question. I'm curious to hear what Sarah has to say, but it's a strange thing. You know, our region, the Cali Baja region is, is, you know, kind of the quote, unquote Nexus or center of, you know, the usmca trade agreement, NAFTA, and the amount of money that's being exchanged on a daily basis, you know, hundreds of millions, if not billions, of dollars a day in this region is sick. It's unfathomable. And so I don't know why we have to clamor so hard to get this issue addressed, but it feels like it falls into the area of border politics. And you know, I don't you know, my place here is not to talk poorly about anyone. But if I look at the governor and he doesn't want to get into the river, so to speak, you know, at least not publicly, he hasn't really been willing to come here and, like, put a stake in the ground and say, Hey, there's an issue here, and we're going to fix it. I haven't seen that from him, you know, and we haven't seen that from the Biden administration either or previous administrations for that matter. And so I don't know what's happening in this region, but for whatever reason, it's okay for our predominantly community of communities of color along the river valley to endure this.

Grant Oliphant 24:20

Sarah, what about you?

Sarah Davidson 24:22

Yeah. I mean, I would just add to that that I think we all know that if this were happening in more affluent areas of the county, it would not have been allowed to go on this long. So it's hard to pinpoint exactly what the hesitation is. But I think one of the tricky things about this watershed is that it's divided into so many different jurisdictions, and that makes it very easy for people to point the finger and say, That's not our problem. It's not a state issue, it's a federal issue. It's not a federal issue, it's an international problem. It makes it very easy for people to just kick the can down the road. And not take responsibility for fixing the problem. But of course, the end result is that communities continue to suffer every day. Our economy is suffering as a result, national security is threatened. This isn't simply, you know, an environmental issue, it's it's impacting every aspect of community life and the region here, and we really need everyone to step up and do something so

Grant Oliphant 25:26

point us in the direction of what can be done. Obviously, there's a role for the federal government, there's a role for international diplomacy. There's a role for the state and for politicians locally. But here you sit as community advocates working on the issue, and what do you foresee in the next five or 10 years as your role to turn this around?

Ramon Chairez 25:53

I think we're right now. We're living out our role in this issue, right? You know, especially as advocates, and you know, speaking about it, whether it's locally or whether it's up at up in Sacramento, Sarah is going to be heading to Washington with a group with the mayor of Imperial Beach in the next few days, and so we're all kind of making sure that we're being vocal and keeping this issue kind of in the Media. So that's important to keep the issue alive, because if we don't do that, the path that we're on right now is okay, we're gonna IBWC is saying they're gonna fix the international wastewater treatment plant, but that's gonna take five to seven years. So right off the bat, we're being told you just need to sit tight and wait, and then they're also saying, Well, we're only going to be able to process so many millions of gallons. I think it's like 50 total, right? Right now their capacity is 25 but I don't think they're even doing that. What do I know? So they'll be doing 50 million gallons a day, right? And that's if conditions are right. That's the one thing you know about the river valley, conditions have to be right, right. Like, if there's heavy storms, throw the you know, the game plan book out the window. You know, the canyons release a bunch of sediment, the trash comes through, um, and the, you know, the plumbing Tijuana breaks down or pauses. And so all of a sudden, the the whole river valley is just flooded with all these, you know, all these things. And so we know that it's even on a good day that capacity is not going to be enough. And then we also know that what's coming through the actual River, through the channel and Tijuana into the river, doesn't go doesn't go into a treatment plant. Right now, there's no plan for that right now. It flows through the river valley, into the estuary and out into the ocean. And so there is no right now you there's nothing to look at that you can say, like, Oh, wow. We're actually gonna fix this, what we're doing and what we keep hearing, and I don't want to dismiss what the progress that's been made between Mexico and the US in terms of the plant repairs that they're doing in Mexico, and the plant repairs that we're doing here, all the infrastructure repairs that are going to happen on both sides of the border. I don't want to dismiss that, but let's be clear, that's happening because it wasn't done before. It's like you weren't taking care of the house before, and now you want to be applauded because you're making up ground,and that's not good enough

Grant Oliphant 28:33

when, in fact, we're still behind

Ramon Chairez 28:34

Exactly.

Grant Oliphant 28:35

Yeah, Sarah,

Sarah Davidson 28:37

I would say that you know one thing that we're doing, all of us collectively, is building a social movement to create change here, and that social movement gets stronger every day. And you know, while the problem is getting worse every day, I do see hope in the fact that more and more people are becoming aware of this issue. More and more people are joining this effort, and it will take all of us in every sector bringing our own skills to this fight, and so we can finally solve this problem and then maintain those solutions, which has been the problem in the past that Ramon is talking about, infrastructure has been built, but not maintained, environmental injustice here looks like neglect and lack of investment in these communities and the infrastructure to protect them. So we have to build up the political will to do that. We have to get our governments to invest money, not only in building, you know, not only in providing, I would say, immediate relief for impacted communities that are facing daily health issues, but also building the infrastructure to solve the problem and then really creating ongoing funding sources to maintain that infrastructure so that we don't find ourselves here in another 10 years.

Grant Oliphant 29:58

Yeah. Well, I want to thank you both for spending time talking about this, and I love how you're thinking about the future. Couldn't agree more, from our perspective, about the importance of keeping the issue on the table. In fact, I Ramon, I want to tie it back to the story you told about was it your your father, your father going back and coming back with wet pants, and that felt like it had to be done in secret and and so much around border stuff gets shrouded that way. And really, what you're both talking about as community advocates is daylighting a problem that's been hidden for a long time, and it's kind of a beautiful metaphor to leave us with. And I just want to thank you for the work you're doing and for the opportunity to work alongside you on it.

Ramon Chairez 30:54

Thank you for that, Grant. You know, one of the things that I've that I've said and shared with colleagues is we're waiting for someone to really embrace this at a higher level, to say, hey, we're gonna Yeah, let's accept what this is, yeah, and let's just go for it. Let's fix it

Grant Oliphant 31:10

and no more. Oh, well, we tried.

Ramon Chairez 31:12

Well, you have to wait

Sarah Davidson 31:14

someone else's problem,

Grant Oliphant 31:15

right? Yeah, exactly.

Ramon Chairez 31:16

Thank you Grant appreciate it.

Sarah Davidson 31:18

Thank you very much.

Grant Oliphant 31:18

Thank you both. Yeah. Wow, Crystal, there is just so much there.

Crystal Page 31:27

Yeah, and I think they mapped out the big picture for us. So should we go to the

Grant Oliphant 31:32

Yeah? Why don't we do the next segment and then maybe reflect on our takeaways at the end?

Crystal Page 31:37

That sounds right.

Grant Oliphant 31:38

All right, let's do that. Yeah?

Grant Oliphant 31:39

Lesly, Kapili, welcome. Thank you for being here. It's really a pleasure to have you.

Lesly Gallegos-Stearns 31:46

Thank you for having us.

Kapili Pasa 31:47

Yeah, thank you.

Grant Oliphant 31:48

And I should say thank you for the work that you're doing on this issue. We're going to be spending some time talking about that, but before we get into the organizational perspective and everything you're doing and how you see the issue, I want our listeners and people who may be watching this to have some sense about why it matters to you and how you came to care about it. So would you each just briefly say a word about that?

Lesly Gallegos-Stearns 32:14

Yeah, I guess I can start. Yeah. So I grew up in Imperial Beach. And my parents were originally from Tijuana, Mexico, and they thought that moving to San Diego would be the move for a better way of life and a better environment for me to grow up in. So we moved to Imperial Beach, and the first 10 years of my life, I lived right next to the estuary, which was a privilege, but also it was seven of us cramped into a two bedroom apartment close to the beach because we wanted to be close to the beach for the access, but it wasn't convenient to be living in such a small space. But just growing up going to the estuary or the beach and creating memories with my family and most of my grandparents. It was my grandpa, rest in peace. He showed me to care about nature and taught me about different plants and all these animals. And it sparked some concern to me when I would see dead animals washed up on shore, and also the caution or do not enter, or like there's a risk of bacteria in the water, and just being like, like, is this normal, like, Does this happen at other places? And as a kid, it just struck me, because I cared about all these animals and like the natural area that I lived in to pursue a career, because it just how is a place so beautiful and biodiverse, polluted and not cared about, or why isn't there clean water or solutions being addressed?

Grant Oliphant 34:09

So it was both personal and you had these deep questions about Kapili. What about for you?

Kapili Pasa 34:17

Similar to my colleague here. I grew up in Imperial Beach. I was born and raised there, and my family originally is from Hawaii, and so part of our culture is the water. So I found that community in Imperial Beach participating, you know, in junior guards, growing up surfing in IB being in the ocean with my family, with my friends. And so it has always been a very integral part of who I am as an individual, and I got the privilege of getting to pursue that in my career. So I've started off as an ocean lifeguard, you know, in 2015 and just continued in that career from here and segueing that into my professional life, I get to lead our ocean lifeguard team at Camp Surf. But it's not just about the waterfront for us. We run a whole entire program around environmental stewardship and positive youth development, which is severely impacted by this issue, and so it's really fueled the fire for some of the passions and the reasons why I'm involved today, but yeah, we're losing out on the next generation of life savers, or just losing out on the opportunity to give the next generation of kids the knowledge and the passion that I have for the ocean, because I truly believe in the life altering power of the ocean and the tools and the resources that it can provide for, you, know, a healthy community and lifestyle and everything

Grant Oliphant 35:45

I, I would love for you to both say a little bit more about why it matters along the lines, Kapili, of what you were just saying, Because I, I think it is disconcerting and infuriating for many of us. When we hear this issue being dismissed as a surfing issue or an amusement issue or a lifestyle issue, it's not at all how you just described it and and what do you want people to know about the breadth of this issue that is so that makes it so much more important than they may realize.

Kapili Pasa 36:27

When I think about about the next generation of leaders, or just about the children in my community, or the youth that come through our program at YMCA Camp Surf, I think about the disservice and the long term effects that this is having on them. Part of the reason why I chose the trajectory of my career is because I was introduced early to what the ocean is and how to navigate it safely, and how to not only find comfort, but the competence and the confidence to then share that with my community, and so I was blessed to be part of a program in 2017 with Camp Surf called rip runs, where we get to the trained lifeguards, get to teach kids how to go into a rip current and how to navigate that safely, and we rely on them to then take that home to their families. And so when their families are out at the beach without Camp Surf lifeguards, they have that ability to keep their entire family safe, or have the ability to know what to do if the situation occurs where there is unsafe situations, and I know that as a first responder, that is something that is a passion for the rest of my life. I'm going to be learning and I'm going to be teaching people safety around that. And I don't get the opportunity to do that. I don't have six year olds or teenagers who I get to train and build their passion and fuel that for them so then they can become the next first responders or things like that.

Grant Oliphant 37:59

That's great. Leslie, what about for you?

Lesly Gallegos-Stearns 38:01

Yeah, I think, when I think about the effects that this issue has had in my community, and not just Imperial beach, but San Ysidro and the inland communities, I think about the health impacts because I developed asthma, and I feel like part of the reason why I developed asthma was my exposure, not just to this smog and the smoke of living near the border, but also the untreated sewage odors that have been ongoing for decades, and like residents have complained about that for so long. And why is it that barely now they're getting that attention. When I used to work in San Ysidro with air quality, residents would always complain about headaches and nausea and not being able to concentrate or sleep at night, and I've been having to live with that for as long as I can remember. So it's not just access, it's also health impacts and a degrading quality of life that is at risk if the water is not fixed.

Grant Oliphant 39:11

Yeah, I just want to underscore this to because I think it's such an important note that you're both sounding. This is a it's about an issue, but it's also about a cultural dynamic and a symbolic one in a culture, and it's about empowerment of young people and empowerment of families, and it's about public health and about quality of life and state of mind. Those are just some of the things you just described, and I so when we're thinking about, what do people forget when they hear about this issue? There's a lot that people forget. Kapili, I know, with the trans boundary Coalition for advocacy and healing, there's a range of ages and folks working on on this issue. What do you see happening with people working across their differences on this issue, and, and, and how, how do you see that playing out?

Kapili Pasa 40:09

I see we, as a as a facility, YMCA camp, serve, get to welcome a lot of organizations who are doing a lot of different work, and we've welcomed in people who are doing, you know, photo exhibits, all the way to art shows, all the way to just coalition meetings, round tables and things like that. And so what I am seeing is a bunch of different avenues for advocacy that is really inspiring. I'm seeing, you know, young people recruit other young people to come to these meetings, to get involved. I'm seeing that access to policies and procedures and change makers and decision makers. I see that bridge being a little bit shortened, and I see the next generation kind of be inspired to continue in those advocacy efforts, because change is possible, because we are as a as a coalition, as a community, we are gathering together, and there is movement, and we just need it to continue.

Grant Oliphant 41:06

Yeah, thank you for that. Leslie, same question for you. Yeah,

Lesly Gallegos-Stearns 41:11

I think being part of this coalition is a great way to just everyone that has so many ideas and everyone that's been trying to hit different parts of this wider issue and solutions as well. It just brings us together on this, because we all care about clean water, and we all care about having safe and healthy beaches, and the fact that clean water is a basic human right, and we all want that. So just the all the different groups and organizations and government entities caring about it, is great to see, because I feel like back when I was younger, there wasn't much of that, or I didn't notice it, at least, but it feels great knowing that now we have this and there's a group of committed people trying to actually do something. Yeah,

Grant Oliphant 42:11

so I'm curious to hear from both of you about, okay, here's the setup, and I'm gonna I hesitate to repeat this, because it's almost like bringing into the room the negative energy, but I think, I think we need to acknowledge it so often, when people talk about what's going on in the Tijuana River Valley, they say, well, that's been going on for decades. They say, it's a international issue. It's bigger than us. It's a national issue. You know, as other people have said, there are lots of places to point fingers at, and which makes it seem like it's too complicated to address. And so it's long term and it's complicated and it's messy and it's expensive and there's money at stake. We can be confident of that, and and so therefore they say it can't be solved. You don't buy it. Why don't you buy it?

Kapili Pasa 43:07

The alternative is unacceptable. If we do not do anything, that is unacceptable. So I refuse to accept to do nothing. It doesn't matter that the battle is hard. It doesn't matter that there might not be progress or it feels difficult. I apologize if I get a little emotional about this, but I refuse to accept anything less.

Grant Oliphant 43:30

Thank you. Thank you for and thank you for being real about it, because I think that is fundamentally the answer. Leslie,

Lesly Gallegos-Stearns 43:39

yeah, I think, I mean, the alternative would be to do nothing, and I can just imagine how terrible it might be like so many people that don't have the privileges or the money to be able to move even exist today, where there's communities that live that are In the front, like in the front, of this issue being affected daily. And I include myself in that as well, because I have to deal with the sewage odors almost every night, and like the health impacts that come with it, I feel like we have there's hope, and a lot of the younger generation are they, they have that hope and that energy, and it's great to see that, and I feel like it's part of who I am and what I'm meant to do to be part of that solution and to bring the solution forward, because I want to see a future with clean water and see that community and that ecosystem thrive.

Grant Oliphant 44:49

Yeah. Thank you so much for embodying that both of you and those answers are powerful, and I feel like I just want to say as affirmation for anybody who may. Watch this video or be listening to this podcast. I think another thing I would add, since I asked the question that made you cry, is is, this is the very definition of a solvable problem. It's not just that the answer is unacceptable, it's that we actually know what to do and and what should motivate people is seeing the passion that that people like you are bringing to this work, and the refusal to accept all the excuses. So I actually believe that we've known for a long time how to solve this problem, but the thing that's ultimately going to drive the change is the refusal to accept the excuses any longer. So I just, I just feel like I need to say that to make sure we don't leave that on a negative or downer note. I am, I'm curious to know the role of of organizations like, you know, like camp, surf and and, you know, in, sorry, and San Diego Coast keeper, I knew I trip on this question, but I'm curious to know how you see these organizations playing an important role in fostering a concept of economic stewardship that gets people motivated to want to engage on the issue, and not just what they would normally learn through these organizations.

Kapili Pasa 46:30

So part of our core curriculum at Camp Surf is an acronym called I care, and really quickly it's i, c, a, r, e, the i is in relationships. C is cycles. That's life cycles, the water cycle. A is one of my favorite. It's awareness, appreciation and action. R is relationships, and then the E is energy. And so we teach about all of these things, but incorporated in that is sort of these long term environmental stewardship goals. We are teaching the fishermen how to fish. Essentially, we're not just giving the fish, the hungry man a fish. So in that it's we're really looking to empower the people who are coming through our program and our program participants to not only be aware of what is going on, but to appreciate the environment that we're in, we are lucky to be right in the middle of an endangered marshland, and so the direct contact that our guests are getting is with endangered species, right? We do get to show them the impacts of pollution right on our beach, and I think that also goes long term, because they're taking that home to their communities. We get a lot of people from Arizona or nationwide. So it's not just the local residents, but we're sharing the issue that's happening on our beach everywhere. And so I think that is one way we're able to play a big role in that.

Grant Oliphant 47:56

Great. Thank you. Leslie, what about for you?

Lesly Gallegos-Stearns 47:59

Yeah, I think when I think about the impact of environmental and outdoor nonprofits and organizations, I think about the educational component they offer to the public, but also like advocacy tools, because when you know The facts and you're educated on an issue, you'll feel more knowledgeable and empowered to do something like with my programs with water quality sampling, we're out in the field. I show them, this is a pollution source, or this area has high bacteria, and they're like, they care about it because they're out there. So I think it's the exposure that people can get to the outdoors and also learn from it empowers them to care and also advocate for that. And like with Coast keeper, having a legal arm also does great, because we can take legal action against a polluter directly, or advocate and work with other groups, and I think with the coalition as well, it's creating more. How would I say this? Like each organization is doing what they can, because we, just one of them. Can't do it at all, especially for something like this. So we're all doing our part, and we're playing, we're putting up the pieces of that puzzle together

Lesly Gallegos-Stearns 48:02

the value of a coalition, yeah, and so I'm just, I'd like to invite you to say a little bit more about the legal piece, because I think that's maybe an element that folks don't normally think about. So how does that come into play?

Lesly Gallegos-Stearns 49:44

Yeah, I think with Coast keeper having a legal team means that we can file citizen lawsuits. So we can sue the government, which we actually are so we. So we're, we filed the lawsuit against the international boundary wastewater treatment plant, and that's something that might have been done in the past, but hasn't done much. So there's, I feel like there's no harm in doing something like that again and putting that pressure on because it it's amplifying the voices of the community and amplifying the issue, but it also means that we can use the power of the law to bring solutions from a different angle.

Grant Oliphant 50:31

I'm curious. I want to I want to give you both an opportunity to close with some thoughts that may be on your minds. But so let's start with what is it that you would like the affected communities who are living through this sewage crisis that's been so long standing? What would you like them to know? What do you want them to believe at the end of the day?

Lesly Gallegos-Stearns 50:55

For me, I'm just thinking back to when I used to work with the community in San Ysidro on air quality issues, a lot of them were either ignored or dismissed when they would bring up the sewage odors because it didn't qualify as an air quality concern, like it wasn't CO two or it wasn't particulate matter. But I I always believed them, and I would always put pressure on other like government entities and my manager and telling them, like, hey, these issues are interconnected, air and water there. They can impact and influence each other, and they're causing health impacts. So there's people that care, and I definitely care a lot, and I feel like when you care you, you won't give up. And I feel like my community, I'm always going to do what I can and be the voice for them, because I know a lot of them don't have the time or the resources to go out and give a public comment or write a letter to their representative. But right now, it's my job to do this, so I'm going to do what I can to be that voice,

Grant Oliphant 52:12

beautiful Kapili.

Kapili Pasa 52:14

I'd really just like to echo that not giving up. This is a long and strenuous and tumultuous journey that we've been on, but I think that together, we are going to go further. I mean, we see it just in the last couple of months alone, the movements that we have seen are historical, and so I I want to encourage our listeners to just get involved, whatever that looks like. If you can educate yourself, if you can attend public meetings, if you can attend events, if you can advocate in any way, please do so and help us fight the good fight.

Grant Oliphant 52:55

Yeah, so let's both. Let's all three. Take a breath for a moment. And I would invite our listeners to do the same. You know, we sort of ended up in a heavy space, and it's because you care about the issue, and I think the answers to the questions lead you there, but I would love if you could for you to add a thought at the end about what gives you hope in this work, what animates you around this work? And it can go back to the magic of the ocean, you know, anything. But I think people need to hear that.

Kapili Pasa 53:38

I think I've really been absolutely blown away at the power of the people the leaders who are leading this advocacy journey for us have been phenomenal and easy to follow. Their passion absolutely has sparked and spread through every single tier, whether that is our politicians all the way down to our six year olds who are writing letters. I just am beyond amazed at the community gatherings and the coming together so we can share resources, so we can educate each other, and so we can make some change.

Lesly Gallegos-Stearns 54:20

Beautiful. Yeah, I think for me, it's that there's a lot of momentum right now. And I know it can seem like a lot in burnout is real, especially like knowing this for your whole life, but it's good to take breaks and step back and like just walking at the estuary, or looking at the sunset, looking at the beauty within all the pollution, like you would, you could go visit the estuary, and you wouldn't think that it was impacted by untreated sewage or impaired water quality, because. There's there's beauty in there. And I kind of just want to say this quote that my friend mentioned to me the day before the rally that was held in October. It's, there's decades where nothing happens, and there's weeks where decades happen. So I feel like this year there's been a lot done and there's still a lot to be done.

Grant Oliphant 55:29

Yeah, beautiful. I mean, change does happen that way often that we push and push and push and push and push and push against the rock or the wall or whatever, and then suddenly it gives so I really want to thank you both for that. Leslie, you had something you wanted to say in Spanish before we wrap up.

Lesly Gallegos-Stearns 55:48

Yeah, I kind of the same quote. I just said, Yeah, but in Spanish, please, Hay decadas en nos que nada occure y hay en semanas y nos que decadas occure

Grant Oliphant 56:02

wish my Spanish were better, and it's on me that it's not but it's beautiful. And thank you both for the work that you're doing. I just have to say that in very short time, you've said some magical, powerful things. And I think as people contemplate the work that's happening. There's a lot in this interview that they will carry with them, and so thank you for the work that you're doing, for being the souls that you are in this work. This is precisely what we need. So appreciate you being here, and I've really enjoyed this conversation. Thank you for having us. Thank you.

Lesly Gallegos-Stearns 56:41

Yeah, thank you

Grant Oliphant 56:42

so Crystal I, you know, like we said, after the first segment, there's just so much to think about here. And I just want to say thank you to our guests for being real and sharing their not just their thinking, but their emotions about how they're experiencing this issue. It was very powerful. And I think for anybody who has any questions about why this issue matters, I hope they listen to or watch this episode, yeah,

Crystal Page 57:11

or play it again and again, yeah, to because they're I think, um, I've heard all of these spoke folks speak over the last several months, but there was something about, like you said earlier, their heart was on the table, the emotion, the connection to why this matters to them. You know, it's not just about a nice beach. It's about a good quality of life for someone's family, right?

Grant Oliphant 57:35

I when I was making notes as we were listening to them, and I've got three takeaways that I would share, and I think we can fill in on these. But the first issue is simply that this issue is real. You know that it is a big and significant issue. Community sees it, they feel it, they know it. They're not going to be gaslit about it any longer. They they they know what they're experiencing, what they're smelling, and what they're seeing, and its impacts are huge for them. And it's emotional, it's personal. It feels like, if they it's it feels like being neglected. Did that strike you as well?

Crystal Page 58:20

It did. I think when Leslie was talking about maybe it was kapili said she's not gonna accept this anymore. Yeah, I think that was the thing that felt different, right? I think about all these newscasters and stuff who talk about 30 somethings and 20 somethings being lazy and not caring. And everything we heard was the exact opposite of that, yeah, Let no one say Millennials or Gen Z doesn't care. Yeah, right. And I felt like, if we all just say, in English, it's enough's enough, but in Spanish, when, like, when you organize with janitors, it's ya basta, enough's enough. Stop it. Right.

Grant Oliphant 59:01

Love that.

Crystal Page 59:02

I think, I think you're right. If we're all not willing to accept this, and we all keep talking about it and demanding more, they're gonna have to, the people in power are gonna have to meet us where we are.

Grant Oliphant 59:12

Well, that's that, for me, was the second takeaway, which is that this is so it's real and it's big, but the second takeaway is it's solvable. No matter what anybody is telling us, this is a solvable problem. And yeah, it's complicated, and there are lots of people involved, but when you listen to the folks that we just had on, yeah, they're talking about the power of their communities to keep the issue front and center. You're hearing them say we're just not going to let go. You're hearing them say this is not acceptable. You're also hearing references to research which is showing that that what they're sensing is real. And I loved actually Ramon's expression of being in the river. They're In the river, they've got the flow around this. And so I think, I think we should view this more and and hopefully persuade others in San Diego to view this as, yes, it's complicated, but it is solvable. And we're we're going to head in the right direction if we decide to,

Crystal Page 1:00:18

yeah, and I think they've already decided that we're gonna go forward. So I think it's get on the bus on this one. And there's a part of me that just feels a solidarity with these folks, that it's just like this is not only not acceptable, but why does it happen to this community, but not others, right?

Grant Oliphant 1:00:40

Well, and that actually, for me, that's we didn't compare notes, but that was the third takeaway, which is that this is fundamentally about who in our community we believe matters, and what comes out in these interviews is that we can't, and it is not acceptable any longer in San Diego to allow a problem of this scope to happen to people because they live in a community we don't, or because they have less money than other parts of the community, or because they're unseen in ways that the rest of the community isn't.

Crystal Page 1:01:19

Yeah, well, and I also hold on to what some of the folks said about they just want a good quality of life, right? Yeah, this was all cleaned up, yeah. Can you imagine how happy people would be? People could get out there and do recreation safely? Yeah, we heard about the YMCA surf camp, and every kid deserves to go to a surf camp and learn. I mean, that's the San Diego way, right? So it's we're missing out on opportunities. That's what I heard from the second set of interviews. So we need to, we need to fix it now.

Grant Oliphant 1:01:51

We are a border town and we are an ocean town, and the entire fate of our community is tied to what's happening in the Tijuana River Valley, whether we want to acknowledge it or not, and I think we will want to acknowledge it more now.

Crystal Page 1:02:06

Yeah, so we'll continue in the next episode.

Grant Oliphant 1:02:09

Yep, and we'll, we'll be, we'll be talking in this series with pediatricians, with others who are working on this issue. We're going to be talking to Dr Mona Hanna, who has experienced exactly what we're experiencing in Flint, and knows the playbook and will talk to us about that. And I think for anybody who is curious about how San Diego can do big things, we're going to map that out in this set of interviews.

Crystal Page 1:02:36

So come back and stop and talk with us.

Grant Oliphant 1:02:38

All right, we're looking forward to it.

Grant Oliphant 1:02:47

This is a production of the Prebys Foundation,

Crystal Page 1:02:50

hosted by Grant Oliphant Co- hosted by Crystal page CO, produced by Crystal page and Adam Greenfield,

Grant Oliphant 1:02:59

engineered by Adam Greenfield production

Crystal Page 1:03:03

coordination by Tess Karesky,

Grant Oliphant 1:03:06

video production by Edgar Ontiveros Medina,

Crystal Page 1:03:10

special thanks to the previs Foundation team. The stop

Grant Oliphant 1:03:13

and talk theme song was created by San Diego's own Mr. Lyrical Groove.

Crystal Page 1:03:18

Download episodes at your favorite pod catcher, or visit us at prebysfdn.org